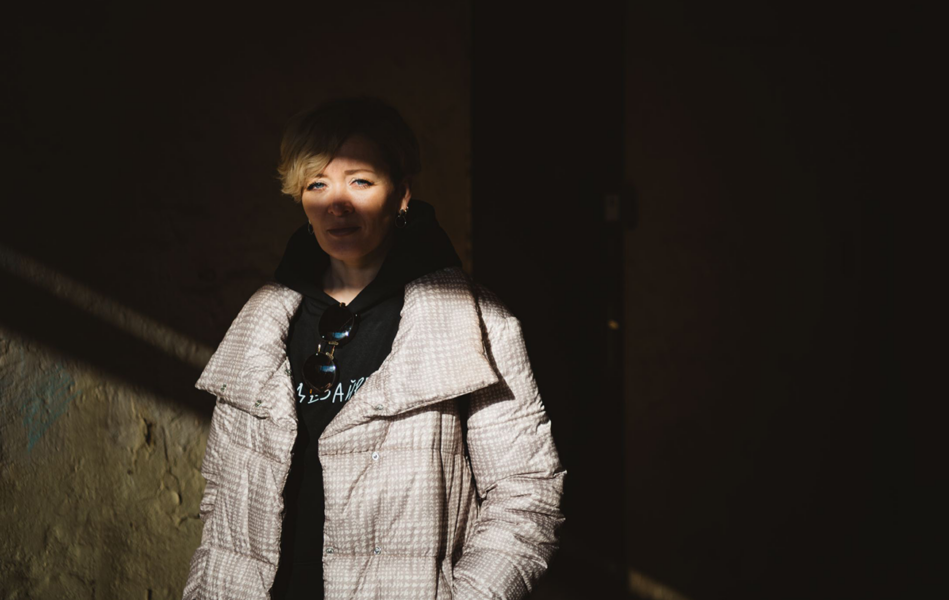

Having spent 2 years under house arrest, a Rostov-on-Don activist Anastasia Shevchenko got a suspended sentence for association with “undesirable organizations.” She became the first person to have been convicted under the new article of the Penal Code.

Anastasia told Glasnaya about her daughter she had lost during the investigation process and how she found out about the hidden camera in her bedroom. She shared her experience of being psychologically pressured by investigators, how she became a different person, and how she managed not to lose her “heart of good”.

First rebellion

I grew up in a family of a military man and a teacher, in a small garrison in Jida village. It’s in Buryatia, not far from the Mongolian border. That’s where I got married, to a military man as well. Our daughter, Alina, was born in 2001. Because of the nuchal cord, I had to have a C-section. My newborn daughter was diagnosed with severe, pretty much incurable diseases. She had chronic central nervous system damage, cerebral palsy, and other diagnoses. The doctors offered us to place her into institutional care. But we couldn’t do it. It was our first child. We never stopped hoping we could find a way to cure her.

When my husband was reassigned to the Egorlykskaya in Rostov oblast, Alina started receiving treatment at the famous Rostov Scientific Research Institute of Obstetrics and Pediatrics. They were working with her for three years but we saw no improvement. When the doctors were discharging her from the hospital, they considered taking her to a special needs school because they provided constant care. But we went home.

Your first rebellion begins when you face injustice.

It was a great injustice that I couldn’t buy prescription medication for Alina. It is guaranteed by law but pharmacies didn’t purchase it on time. I was contacting the Ministry of Health and arguing with staff members in pharmacies, and in the end, I got what I wanted. But it took me an enormous amount of time, and my sick child couldn’t afford to wait for so long.

My daughter was always in bed, she didn’t talk, she was screaming in pain, and cried often. Every day was filled with pain and suffering, I was scared for the child. She didn’t talk, I never even heard the word “mom” from her.

Three years later, we had Vlada, she was born healthy. When Alina was crying, Vlada was crying with her. Then my mom moved in with us. We had to listen to the neighbours’ complaints about Alina crying too loud all the time. We tried to explain that the child was sick. But people wanted silence.

Alina’s health was getting worse every day. At some point, the medicine that was so hard to get stopped helping. Keeping her at home was no longer an option, she needed long-term care. The doctors insisted that I put her in a boarding school for mentally retarded children in Zverevo that is also located in Rostov oblast.

We didn’t have mobile phones back then so I could only call the boarding school by using a payphone. I literally lived near that payphone. I would constantly call them and ask about Alina, and then run home to take care of my second daughter.

We often went to that boarding school. Alina needed food and medication. My mom and I cooked borscht, pureed it with a blender, and spoon-fed her—Alina couldn’t chew the food, she could only suck it. We brought baby food, diapers, and swaddles.

We were planning to take her home regularly but it turned out to be bad for her health. She suddenly developed allergies and got covered with red spots. So we decided to put her under constant medical supervision. We brought her back to Zverevo and kept visiting her there with Vlada. And when we had Misha in 2012, we started taking him with us too. I was a legal parent, I wasn’t deprived of my parental rights.

The turning point

I didn’t know how to keep going but at the same time, I realized my daughters needed me to be strong and healthy. My job became a life-saver for me. Back in 2006, I started working for local television, which was a part of a regional newspaper called Zarya in the Egorlykskaya stanitsa. I worked for 4 years there, covering the work of authorities and ordinary people’s problems.

Then, in 2010-2011, I worked in a local department of the election commission of Rostov oblast. I saw the electoral process from within. But I didn’t work at polling places so I couldn’t see the irregularities and ballot stuffing. I dealt with documents and there was no illegal stuff in that area. I switched to CPRF because I wanted to actively participate in public life, grow professionally, but not within the ruling party. I didn’t stay long there though.

I was looking for my place in the world. I met other activists from Rostov. In 2014, we were trying to revive the Solidarnost United Democratic Movement protesting for the release of Nadiya Savchenko and Oleg Sentsov. Our movement objected to the installation of the monument to the heroes of the Donbas because we were against the promotion of fratricidal war. When they killed Boris Nemtsov, it was the turning point for me. I couldn’t stay home.

Since then, I started taking it seriously. I realized that

I have to fight for the truth myself. Because behind all that red tape, there are people’s lives that are dependent on it, like that of my daughter Alina.

I chose Open Russia. There were activists from different regions, it was a good match, we understood each other well. I’m not going to disclose their surnames, I don’t want them to be arrested like me. In 2017, I became a regional coordinator. A lot of people asked for our help. We worked with the restitution of church land, urban transport development, and urban planting.

In 2018, they opened two absurd administrative cases against me. The first one concerned my participation in the debates with Igor Tretyakov, the United Russia party representative, that took place in Taganrog in 2017. How can you arrest or fine someone for taking part in the debates? It is a normal form of political dialogue. The second administrative case was opened because of the seminar that happened in 2018 before the election for the Rostov region Legislative Assembly. Voting is my right, the same goes for participating in seminars. I had never broken the law. And all of a sudden they decided to fine me.

As a matter of fact, they never gave me reasonable answers as to why they opened those cases and fined me. I was sure they would not dare to fabricate a criminal case. I didn’t even attend uncoordinated protests because I realized I could get fined and I would have to pay those fines. I have three kids and a mom that I had to support. I didn’t see any danger. And I wasn’t dangerous either. But someone decided otherwise.

A hidden camera in the bedroom

At some point in summer 2018, I felt like I was being watched. Sometimes I saw complete strangers near my house. They were standing there looking at me from time to time. I would occasionally tell my friends, “I think I’m being watched”. And we would start laughing about it. Why would anyone need to follow me?

And only later, in criminal case files, I saw the pictures of me sitting in a cafe or walking down the street. I didn’t do anything criminal on those photos.

They installed a hidden camera in my bedroom. Centre E operatives arranged it with my landlady at the time

I don’t know why she agreed to do that and how they forced her. They will just have to live knowing what they did for the rest of their lives.

I found out about the camera already during the investigation. It was there above my bed for 4 months, from September to January 2019. Nothing sensitive was happening in my bedroom. My husband and I stopped living together a long time ago, my family is my children and my mom. The investigator then asked me about my relationship with Khodorkovsky: on the tape, they heard me talking about the dress I was going to wear to the conference in Prague. Khodorkovsky was supposed to participate in the conference, too.

In order to collect evidence, a regular audio tape is enough, they could just install a microphone. But they wanted to get not only the conversations I was having but also the visual materials. I think they put the camera for a particular purpose: in case they didn’t get any materials to start a criminal case, they would show incriminating videos on the NTV channel or some other media.

Any person wouldn’t be pleased to learn they are being watched in their bedroom. I believe they did it to humiliate me and exert psychological pressure on me and other activists.

“Shevchenko, out!”

January 21, 2019, early morning. Monday. I got my son Misha for school, as usual. We left our apartment and saw a bunch of people in the stairwell. I don’t remember how many there were. Someone asked me not to close the apartment door. They were purposefully standing there waiting for the door to open: if they just rang the bell, I could have not let them in. And they needed to enter my flat at once.

They were searching till 1 pm. They were dropping my stuff on the floor and took everything that could be used against me. They got my pens and “Open Russia” rubber bracelets, documents, my passport, phone, laptop, two tablets—my mom’s and mine.

Children were terrified but they tried not to cry. Afterward, I found out Vlada was crying that night and my mom got high blood pressure.

I urgently needed a lawyer. They let me make a call. I called every lawyer I knew but it was early in the morning and, unfortunately, nobody picked up. Open Russia found Sergey Kovalevich, a Rostov-based lawyer, and he immediately agreed to defend me in court. But we managed to meet only in the Investigative Committee before interrogation.

Then they took me to the temporary detention center. It was very hard for me. I had to get used to new terms and to the feeling that I was an object that was told some words it couldn’t understand.

— Shevchenko, out!

The word “out” was the most disturbing in the detention facility. It meant they were taking you somewhere and then brought you back.

Two days later, on January 23, the guard came to the detention facility and shouted, “Out!”. And they took me to the court. We came from the back door. Then they brought me down the stairs: I found myself in a deep basement. I never knew there was a basement at the Leninsky District court. It was grey, grim, and lifeless. The atmosphere could easily break a person down. There were a few iron cages, they placed me in one of them. The guard was standing near me. I spent about an hour on the bench in the cage. There were writings on the walls: someone wrote, “Sorry mom,” the other scratched the wall with the numbers of Criminal Code articles.

On my way to the courtroom, I was escorted by six security guards. They explained how to behave in the cage and how to put handcuffs on and take them off.

I asked the court not to restrict my freedom of movement because I had to take care of my three children and my mother who suffered from hypertension. It was the first time I publicly spoke about Alina, my sick daughter. She was going to turn 18 soon and I had to place her in another facility, the one for adult persons with disabilities. That’s what Russian law requires.

But the judge read, “poses a threat to the constitutional order of the Russian Federation and can flee abroad” and imposed a pre-trial restraint in the form of house arrest for a month and 25 days.

I was forbidden to leave my apartment, use my phone and the Internet, and talk to people. The exceptions were my close relatives, lawyers, investigators, the prosecutor, and the judge. Only the investigator could permit me to see a doctor. But it wasn’t me who got sick, it was Alina.

“I managed to see my daughter still alive”

Nobody could reach me through the phone—they took it from me during the search. They called my husband from the boarding school in Zverevo, and he called my mom. They informed us that Alina had obstructive bronchitis. It happened many times before—she would get sick and I would come immediately to take care of her. And she always got better. That’s why the staff started calling me again.

But that time, I couldn’t come. I had to get permission first. My lawyer filed a motion to visit my daughter straight away. But they didn’t let me see her right after. I was only allowed to call the school and get updates on her health. In the meantime, Alina went to the city hospital. She was there alone, without me. There was nobody who could look after her. Medical personnel don’t have to spend all their time with patients and feed sick children. It’s parents who do those things. But judge Ischenko (I will never forget this last name) considered me to be too dangerous to let me go to the hospital to see my child. I think at the time, the plan was to restrict my freedom of movement as much as possible.

I remember January 30 in detail. I was at the Investigation Committee till 6 pm hoping they would let me visit my daughter. But instead, the investigator filed criminal charges against me.

It was all happening while Alina’s condition was getting worse: she was taken to the intensive care unit from the department of infectious disease. By midday, her condition was characterized as serious, by 3.30 pm it was critical. Alina had a cardiac arrest. She was resuscitated. Only after that, the investigator started requesting documents from the hospital: he needed a paper signed by the chief physician that proved that my daughter was actually in critical condition. It was nearly evening. But I kept waiting for permission from the investigator. Only by 6 pm, he decided to let me see my daughter, but just for 2 days: I had to be back at 6 PM on February 1.

I had to go to Zverevo quickly. The problem was I didn’t know how. I was running out of time. So my friend agreed to drive me. She had to sign the papers documenting she was taking me to the hospital during my house arrest. The two of us, without any guards, went to Zverevo. While we were on the road, the investigator was calling me to make sure we didn’t turn to the Ukrainian border (it was about 30 km away from the route). Maybe he thought I would flee.

We arrived at the hospital late at night, and they didn’t let me see my daughter straight away—the attending physician who could give me permission for a visit had already gone home. Only in the morning on January 31 did they let me go to the intensive care unit.

When I entered the hospital room, Alina was lying unconscious. The tubes were all over her. I almost fell because my child was close to death. The doctor caught me and helped me sit down. I managed to see my daughter still alive.

When she died, they immediately took me to the chief physician to make a paper that stated I had no complaints against them. Then we waited until the investigator called and said it was okay for me to go home.

Nobody wanted this to happen that way. Nobody wanted my daughter to die like this. But the red tape, approvals, and mistrust caused the tragedy. I think that if they had let me go earlier and if I had been there for Alina, it wouldn’t have happened. But it was too late.

When I finally came home, my children’s faces were tear-stained—losing their sister really affected them. But the second Misha, Vlada, and mom saw me, they put themselves together. I asked them to get a grip because we needed to organize the funeral. We had to keep a cool head to do that. The investigator came right after. I was afraid there would be difficulties too but he said he would let me go to the funeral.

Nobody was allowed to come up and talk to me in the Northern cemetery. Not even to express their support. I was standing there alone like a leper.

I didn’t have a right to talk to anyone.

Alina was cremated. We keep the urn with her ashes at home. We want to scatter her ashes somewhere in the mountains or over the sea. Because Alina spent her entire life within the four walls.

Adult games

The investigators, the prosecutor, the judges, the guards were people I had not known before. You saw a person for the first time and you realized your life depended on them. I tried to observe them. They were different: some were tougher than others.

Nobody insulted me. I guess it’s because they saw me behave with dignity. They didn’t dare humiliate me. The process took two years, it was impossible to stay defensive for so long. It was like we were playing adult games, the only thing is that it could end badly for me.

They were testing me waiting for me to say something that could be used in my criminal case as evidence of guilt. They were complete strangers who, from the very beginning, were hostile to you. And you had to communicate with them and show them that you were an adequate person, not a criminal. You had to convince them that what they were doing was not worth it. And you had to win them over while they were trying to get more information from you.

They were told to fabricate a criminal case so they did. But I have nothing against them, no hate. They all have families, cats, and dogs. I sometimes see them walk around. And the way they worked with my case, well, they have to live with it now.

Heart of good

The court was extending my house arrest over and over again. Overall, it lasted for two years. They imposed severe restrictions for a year and a month. Then it got a bit better—I was allowed to take walks. I think it’s because the investigation was over and they took my case to court.

These two years changed me. I feel like I’m more mature now. I no longer have a childish attitude. When you find yourself in isolation, you start trying to find the strength to survive. I started writing an autobiography describing each day. Over time, you start forgetting things, and I wanted to keep the memory of the house arrest and challenges my family and I had to face, in detail.

I also was learning poems by heart because your memory gets worse when you’re isolated. I like Boris Pasternak. I can relate to his Nobel Prize a lot:

Lost, like beast incarcerated.

Somewhere—people, freedom, light;

Chase’s clamour—I’ve been baited,

I cannot escape my plight.

And the end of the poem:

Yet, as I approach my passing,

I believe the day is near,

When the heart of good surpasses

Rage and baseness—even here.

I hoped all the difficulties would be resolved and I would go back to my normal life and feel free again. I was living in constant stress for two years though I met “the heart of good” along the way: I met good people. Sergey, the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service employee, was a very good person. He recently died of COVID-19, I feel really bad for him. It was him who took me from the court when they sentenced me to house arrest. Sergey could have acted tough like the others but he didn’t. After the terrible conditions of the detention facility, being held in the court basement, and kept under guard with handcuffs on, seeing human kindness felt like a miracle.

Sergey explained that he was taking me home. And asked which leg to put the bracelet on. I still don’t know why he asked that, I don’t think there was any difference. He just always tried to help. I would say, “I need some fresh air,” and Sergey would open the window. Or he would park the car further from the court so we could walk a bit. Or we would come to the court hearing earlier and stand near the court so I could get some air. I know how bizarre it might sound. But every act of kindness was very important to me. They made me look like I was a violent criminal and didn’t go easy on me. And when I met a person who was kind to me, I was very grateful.

There are certainly cruel people in this system but not all of them are like that.

Suspended

I was sure they would put me in prison. The investigators collected 29 court bundles. It was morally challenging for me. Alina’s death and the last days before the verdict were the hardest. We were discussing it with my family: my mom cried and my children took videos of me. They wanted to remember how I was joking around so they could have a laugh watching it later.

The capture on the mug I gave to my son Misha says “Smile!” That’s my motto. I asked him not to be upset if they put me in jail. And asked him to look at the caption every morning and smile. He’s still using it. I also sent him a few voice messages about how much I loved him. And asked him not to argue with his sister. But he listened to them only three days after the sentence.

Before my last trial, I made video instructions for mom and children. They are about household stuff: how to turn on the oven, what to do if there’s a power cut or the tap is leaking. Neither my daughter nor I delete these instructions from our phones because the process is still not over. They can replace the suspended sentence with a custodial one at any time. I hope it won’t happen.

I took my bag with me to the last hearing. I think it was small. Vlada helped me pack it. She was very worried so she kept putting different things in the bag. «Don’t forget this, and don’t forget that.» She went to the store and bought books and notebooks for me. Until the last moment, she was worried and kept asking, «Did you pack everything you need?» I also gave her instructions on how to bring packages to the pre-trial detention center if I was convicted because a convicted person is immediately taken to the pre-trial detention center after the verdict.

Vlada is turning seventeen in May, she is in the tenth grade. During these two years, she matured a lot, and she can correct me when she sees that I am being «carried away.» She is good at setting personal boundaries. I like that she is not making drama out of our situation. The other day she said that a girl she knew who had difficulties with her mother wrote to her, “I would like to have a relationship like you have with your mom.” And Vlada once told me: “If this had not happened, I would not have been where I am today. I don’t regret anything in life. «

I don’t regret anything either. But there are tragic moments that my family shouldn’t have gone through. They didn’t deserve it.

They were reading out the verdict for almost the entire day, with a short break. The judge spoke so quietly and quickly that I did not understand a lot of things. Seven-year-old Misha was so tired that he started falling asleep. When they said «suspended,» my daughter rushed to me.

«I want to be myself»

I was staying silent during my two years under house arrest. People read everything my daughter Vlada posted on her Facebook page, and everyone had their own picture of what was going on. Now that I’m given conditional release, I may not live up to the expectations of other people. Probably, for the first time in my life, I don’t want to meet anyone’s expectations. I want to be myself.

I cannot participate in the elections, observe them, go to rallies—I have been conditionally released and my case was related to politics. I must stay away from all this so I don’t end up in jail. But

today, there are many areas where you can prove yourself as an active citizen. I’m not going to limit myself.

I will take care of my children more. I think we need to pay more attention to our children, to love them for who they are, and to take interest in the process of education. What they are doing with education right now is very, very dangerous. Regulation of educational activities, for example. Everyone, including tutors, can fall under this law. In my opinion, it is impossible and rather dangerous to control all educational activities. As a parent and a teacher, I really care about the topic of education. I am currently giving private lessons.

Children must be protected and educated. I teach my daughter to get information from different sources. It is wrong to obtain knowledge from one school textbook. You need to listen to podcasts, read books, watch movies, and discuss everything with others. This creates a complete picture of the world. And through school education alone, it becomes unidirectional.

This also applies to gender roles. There is this cliché that the greatest happiness for a woman is to get married and have children. Nobody asks her if she wants to get married and have kids. A woman has every right not to want either one or the other—and to do the job where she can achieve her highest potential. Unfortunately, no one listens to women’s opinions, even at school. The girls go to cook, and the boys go to make stools. As a child, I always wanted to make stools. It was way more interesting to me than cooking borscht.

I meet a lot of young people, students, schoolchildren, and I see that everything is fine. I like these people who don’t watch TV, who form their own opinions. They actually seem more mature than me. And these are not the people who will vote thoughtlessly or participate in electoral fraud.

A generational change is coming. It’s inevitable. It is only a matter of time. Of course, I would love to live freely, quietly, and fearlessly. But we’ll have to wait a little.

We are launching The Influential series which tells about women who are changing the social landscape in Russia and taking an active position in life. The Influential is about those who manage to create and contribute to future change.

The material is published jointly with Novaya Gazeta.